Submission to Myanmar Universal Periodic Review 2020 (UPR)

Free Expression Myanmar (FEM) Submission to the UN Human Rights Council on the Universal Periodic Review 2020 Third Cycle for Myanmar

6 July 2020

Introduction

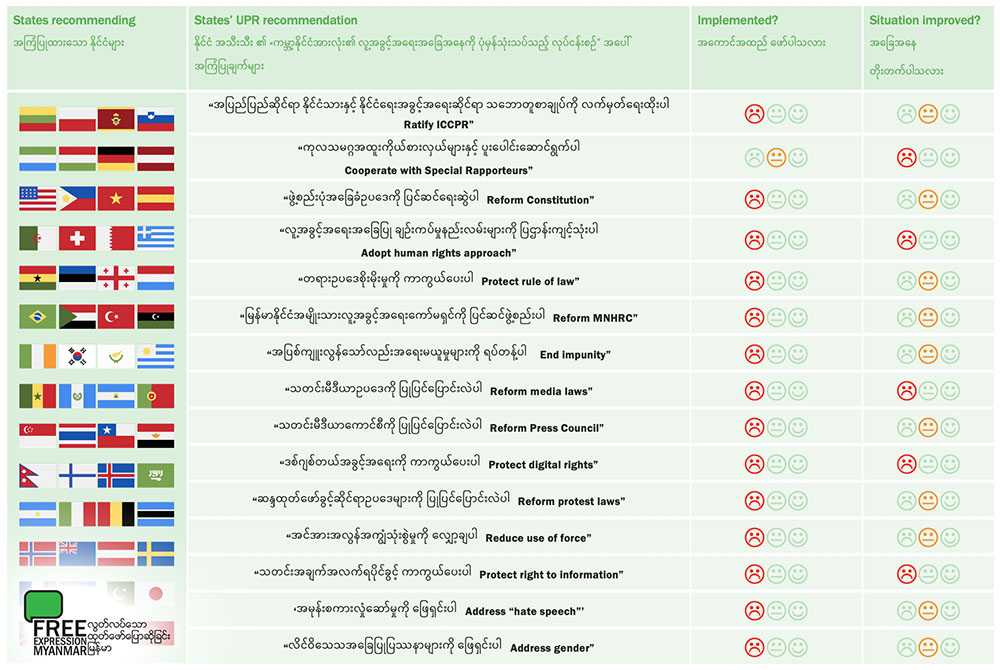

- This submission will focus on FEM’s expertise on FoEI in Myanmar. It will assess implementation of previous UPR recommendations, including progressive and regressive actions taken since 2015. As per the guidance, and as seen in the endnotes, it will prioritise first-hand information from FEM’s significant primary research, as well as FEM’s analysis and recommendations. The submission will be divided up into sub-sections based on FEM’s areas of expertise.

- [Word count: 2810 / 2815]

International obligations

- 27 countries:[1] “Ratify the ICCPR” – No implementation. No change.

The State has repeatedly committed to ratifying the ICCPR both publicly and to the UN.[2] However, the State has not done so and a parliamentary attempt was not supported by the government.[3]

- 10 countries:[4] “Cooperate with UN Special Rapporteurs” – Partial implementation. Regression.

The State has engaged with UN Special Rapporteurs’ communications but has failed to cooperate with them, the Myanmar Rapporteur in particular. The State has also continued to encourage disinformation about and hostility towards the Myanmar Rapporteur, her role, and her statements.

Overarching legal framework

- 1 country:[5] “Improve the Constitution” – No implementation. No change.

FEM led 20 national and international organisations in submitting FoEI recommendations to the parliamentary “Constitution Amendment Committee”.[6] However, the Committee did not engage with civil society and the Committee’s final recommendations excluded any substantive human rights recommendations, including on FoEI.[7]

- 2 countries:[8] “Use a human rights approach when reforming laws” – No implementation. Regression.

Since 2015, the process of legal reform has been opaque, inaccessible, and arbitrary in nature.[9] Over the past year, the State has increased barriers to civil society consultation in parliament, including by ordering MPs not to meet with civil society.[10]Although the Association Law provides that registration is not mandatory, in practice State individuals and institutions will not engage with unregistered civil society organisations.

- 3 countries:[11] “Strengthen the rule of law, legal standards, and judicial reform” – No implementation. No change.

Case law shows that the courts still do not defend FoEI, and indeed the courts pose a significant punitive threat to those facing FoEI-related criminal prosecutions.[12]

- 8 countries:[13] “Strengthen the Myanmar National Human Rights Commission” – No implementation. No change.

The Commission does not prioritise investigations into violations of civil and political rights, including FoEI, and does not consider holding perpetrators accountable to be one of its primary goals.[14] Since 2015, all commissioners have been replaced, without consultation, by the State, and none of the current commissioners have backgrounds in human rights.

- 9 countries:[15] “Investigate and end reprisals and impunity” – No implementation. No change.

Legal, physical, and psychological violence towards journalists and HRDs has increased since 2015.[16] There has been no adequate investigation into the five journalists who have been killed in Myanmar, 1 of which was killed since 2015.[17] The State has also become less willing to address crimes against expression.[18]

Media freedom

- 8 countries:[19] “Reform laws to protect media freedom and freedom of expression” – No implementation. Regression.

Media freedom and the State’s public support for media freedom have both declined since 2015.[20] Previous commitments to amend the News Media Law have been left in opaque limbo and the law continues to interfere in FoEI.[21] No attempt to amend the Printing and Publishing Law, which similarly interferes in FoEI, has been made or promised.[22] The Broadcasting Law was superficially amended in 2018 without any real consultation, leaving all anti-FoEI provisions, such as State control over the broadcast regulatory body, intact.[23] Despite adopting the amendment, the State still has not enforced the Broadcasting Law,[24] preferring to maintain direct control over all television and radio channels.[25]

- Criminalisation of journalism has increased year-on-year since 2015, with most threats coming from the executive and military.[26] Although they were later pardoned,[27] the show-trial and conviction of Reuters journalists,[28] as well as other journalists under national security laws, have significantly encouraged media self-censorship,[29] particularly on topics relating to conflict or other issues that the State finds “sensitive” such as the military, mismanagement, or corruption.[30]

- Criminal defamation laws are the greatest legal threat to FoEI in Myanmar,[31] and most journalists and HRDs remain fearful of them.[32] None of the six criminal defamation laws conforms to basic FoEI standards.[33] The laws do not define defamation, defences are lacking, and sanctions are unnecessary and disproportionate.[34] The laws protect feelings rather than reputations, are used to punish criticism or mockery of politicians and public officials, are based on minimal and unreliable evidence, and attract a 100% conviction rate of punitive imprisonment.[35] In response to FEM’s decriminalisation campaign and public pressure,[36] the State superficially amended two of the five laws,[37] but then continued to adopt a sixth criminal defamation law without proper consultation.[38] During the legislative processes, the State reacted to public pressure by effectively excluding civil society,[39] as well as limiting MPs’ ability to consult, prepare, or participate.[40]

- 1 country:[41] “Ensure the independence of the Myanmar Press Council” – No implementation. No change.

The Council continues to be dependent on the State primarily because the State selects and dismisses Councillors. Most journalists believe the Council has a low level of success in defending media, and in some so-called “hot” cases the Council has avoided actively supporting the journalists involved.[42]

Digital rights

- 1 country:[43] “Ensure internet regulation complies with human rights standards” – No implementation. Regression.

Since 2015, the State has attempted to further restrict FoEI in the digital space.[44] Following FEM’s campaign in partnership with civil society, the Telecommunications Law was superficially amended without proper consultation and the amended law continues to interfere with FoEI.[45] A proposed amendment to the Law Protecting the Privacy and Security of Citizens would if adopted add yet more criminal FoEI restrictions.[46] The proposed amendment is in opaque limbo. The State has initiated the development of a “cyber-crimes framework” although it is as yet unclear whether this will include further criminal interference in FoEI, via for example a seventh criminal defamation provision. No attempt to amend the Electronic Transactions Law, which interferes in FoEI, has been made or promised.[47] Despite the proposed amendment to the Law Protecting the Privacy and Security of Citizens, the State has not attempted to legislate to protect online privacy or personal data, or to regulate communications interception, all of which lack a legal framework.[48]

- The State has greatly consolidated control over access to the internet since 2015. The State gave a military conglomerate a telecoms licence, together with regulatory leeway in order to establish a large subscriber base, effectively reversing earlier deregulation which saw foreign private providers both gain market dominance and vastly increase internet access.[49] As a result, the State has regained direct authority over more than half of all mobile subscribers, which, combined with the lack of privacy, data protection, and communications interception safeguards, has given the State unprecedented opportunities to surveil the public and interfere with FoEI.[50] Not content with authority over more than half of mobile subscribers, the State has also further interfered with FoEI by directing telecoms providers to effectively cut off millions of mobile telecoms subscribers who do not disclose their official IDs when registering a SIM card.[51] Many marginalised groups do not have official IDs, and others are concerned about the risk of State surveillance and interference in FoEI.[52]

- In 2019, the State activated a previously unused provision in the Telecommunications Law, directing mobile telecoms providers to shut down access to the internet in conflict-ridden Rakhine and Chin States.[53] The shutdown directive has not been published and the State has only ambiguously justified it in a short statement referencing vague and overly broad national security concerns.[54] Despite FEM’s joint campaigns and widespread public awareness,[55] the shutdown is now the world’s longest and currently restricts internet access for 1.4 million people.[56] In 2020, the State activated another previously unused provision in the Telecommunications Law, issuing a series of directives each ordering telecoms providers to block access to certain websites.[57] In a repeat of the interference in FoEI seen during the shutdown process, the blocking directives have not been published and only been ambiguously justified with references to “fake news” and national security concerns. Although the directives have not been published, tests have shown over 2,000 websites have been blocked so far, including news websites and pro-Rohingya websites.[58]

Right to protest

- 5 countries:[59] “Reform laws to protect the right to protest” – No implementation. No change.

Since 2015, at least 229 individuals have been convicted for their non-violent protests, mostly under the Peaceful Assembly and Peaceful Procession Law which interferes in FoEI by criminalising protesting.[60] Following FEM’s joint campaign, a superficial amendment of the law replaced “permission to protest” with a vague “application to protest”.[61] Most police interpret the amended law as meaning protesters must abide by all the police’s directives on locations, timings, and even slogans, else the application is not accepted.[62] Similarly, if protests deviate from the accepted application, for example by protesters shouting new slogans, the application is voided.[63] A rejected or voided application renders the protest unlawful.[64] Spontaneous protests also remain unlawful in effect because protesters cannot apply in advance.[65] Those who organise or participate in unlawful protests can then be arrested, and all those arrested face collective culpability, long and slow trials, and a 100% conviction rate.[66] Another proposed amendment which would further interfere in FoEI by requiring protest organisers to include information about funding sources in their application remains in opaque limbo.[67]

- 5 countries:[68] “Reduce intimidation and excessive use of force aimed at protesters” – No implementation. No change.

The vast majority of protests are non-violent.[69] However, the State’s primary aim appears to be shutting down any protest that deviates from what was agreed in an accepted application, rather than facilitating non-violent protests.[70] As a result, the State’s preparations are usually unnecessary and disproportionate, and therefore threatening to observers.[71] The State also uses unnecessary, disproportionate, and excessive force to shut protests down, exploiting tactics that at least recklessly if not intentionally injure protesters.[72]

Right to information

- 5 countries:[73] “Reform the legal framework to protect access to information and stem corruption” – No implementation. Regression.

Since 2015, the State has adopted laws, policies, and practices which actively control, limit, and block access to information.The State controls all television and radio channels,[74] bans the media from moving freely or accessing public institutions,[75] arbitrarily shuts the internet down,[76] and blocks news websites.[77] The long-promised Right to Information Bill has remained in opaque limbo since 2015. Instead, in the wake of the Reuters case,[78] the State quickly adopted a National Records and Archives Law which bolsters the Official Secrets Act, furthers State secrecy, and interferes in FoEI.[79] The law allows a “strictly confidential” 30-year classification to be applied to any information without safeguards or an independent oversight body.[80] The law does not recognise the public’s right to access government-held information, including non-classified information.[81] Any requests for information must be individually approved by a government supervisory body.[82]

- Anybody who tries to circumvent these information barriers and exercise their right to FoEI is criminalised, for example under the Unlawful Associations Law,[83] or Official Secrets Act.[84] Although the Anti-Corruption Commission has ruled against several powerful individuals accused of corruption, Myanmar’s six criminal defamation laws, which include the Anti-Corruption Law itself, dissuade sharing and accessing information by criminalising whistleblowers.[85] Amendments to the Telecommunications Law and Anti-Corruption Law have not given any protection to whistleblowers.[86] Just recently, the State’s COVID-19 response has included further criminalisation of healthcare whistleblowers.[87]

- In addition to creating barriers to information, the State has sometimes capitalised on low levels of public media and digital literacy by disseminating biased or manipulated information, commonly known as propaganda or disinformation.[88] The State often justifies this action under the guise of countering “fake news” spread by the media, civil society, and the international community.[89] Examples of large systematic attempts to disinform the public include the State’s domestic distortion of alleged atrocities in Rakhine State, and distortions of the International Court of Justice case.[90]

Discrimination and incitement

- 34 countries:[91] “Address discrimination, incitement and ‘hate speech’” – No implementation. No change.

- Since 2015, the State has not made any significant attempt to counter incitement to discrimination, hostility or violence. The proposed Protection Against Hate Speech Bill, which included vague and overly broad definitions of “hate speech” that would interfere with FoEI, but did not include provisions for promoting tolerance of diversity and pluralism, remains in opaque limbo.[92] The State established the Rakhine Commission, led by Kofi Annan, to investigate allegations of atrocities in Rakhine State. FEM welcomed the Commission’s recommendations specific to media freedom, right to information, and incitement, but none of these have yet been implemented.[93] The State has however issued a “hate speech” directive just before a reporting deadline given by the International Court of Justice.[94] The directive includes vague and overly broad definitions of “hate speech” as well as vague obligations which could be misused by officials to protect powerful groups from criticism, rather than protect minorities with protected characteristics, and therefore serves to interfere in FoEI.[95]

- FEM has campaigned for the State to implement the UN Rabat Plan of Action in order to address discrimination and incitement.[96] However, the State has not created the recommended substantive, systematic, and multi-sectoral programmes to encourage tolerance of diversity.[97] Political leaders, the education sector, and the State-controlled media have at best made limited and arbitrary attempts to encourage some minority customs.[98] At the same time, the State has sometimes perpetuated a nationalist public narrative according to which only State-selected minority customs and groups merit recognition, and that all others are a conspiracy to undermine symbols of the State or to secede.[99]

- 11 countries:[100] “Address gender-based violence and discrimination” – No implementation. No change.

Women HRDs and journalists still face significant gender-based violence in reprisal for exercising their right to FoEI on on taboo topics that challenge patriarchal power.[101] These taboo topics include: campaigning for the rights of lesbians, bisexuals, and transgender people; challenging sexual violence in conflict; promoting sexual and reproductive rights; and advocating for women’s participation and leadership.[102] Gender-based violence in reprisal for exercising FoEI is common and includes attacks on life, bodily and mental integrity, personhood and reputations, and privacy.[103] Attacks come from all parts of the government and security services, as well as from community and family.[104] The proposed Law on the Prevention of Violence Against Women, developed in March 2013, remains in opaque limbo.

Recommendations to the State

- Ratify the ICCPR and its Optional Protocols.

- Cooperate fully with the new Special Rapporteur for Myanmar.

- Amend the Constitution to protect the right to FoEI in accordance with international human rights standards, and prohibit prior censorship.

- Implement a clear, open, and inclusive consultation framework for all future laws and amendments, including removing any de jure and de facto barriers to civil society accessing and engaging with the State.

- Support and accelerate judicial independence and training in international human rights standards including FoEI. This should include applying constitutional law and developing new sentencing guidelines.

- Adopt the following laws in accordance with international human rights standards and overriding all other laws:

- Right to information law, including whistleblower protection.

- Civil defamation law, effectively decriminalising defamation.

- Public service broadcasting law, replacing all State media.

- Privacy, data protection, and communications interception law.

- Gender-based violence law.

- Amend the following laws to bring them into accordance with international human rights standards:

- Broadcasting Law, specifically regulatory independence and an end to State media.

- Electronic Transactions Law.

- Myanmar National Human Rights Commission Law, specifically independence.

- National Records and Archives Law, specifically access to and classification of information.

- News Media Law, specifically independence of the Myanmar Press Council.

- Official Secrets Act, specifically criminal sanctions.

- Peaceful Assembly and Peaceful Procession Law, specifically application requirements and criminal sanctions.

- Penal Code, specifically provisions on sedition, defamation, blasphemy, association, and assembly.

- Police laws, specifically relating to the use of force.

- Printing and Publishing Law, specifically media licencing.

- Telecommunications Law, specifically defamation, shutdown, and blocking provisions.

- Unlawful Associations Law.

- Enforce the Broadcasting Law, providing licences to independent community and private providers.

- Order prosecutors to:

- Adopt new and strong guidelines for a public interest test for all prosecutions.

- Conduct new transparent, prompt, impartial, and efficient investigations into all killings of journalists and HRDs.

- Investigate and prosecute police corruption and misuse of power.

- Order the removal of any de jure or de facto barriers to access to conflict areas for journalists and HRDs.

- Order all public officials to refrain from bringing criminal complaints against journalists and HRDs.

- Order the end to the internet shutdown and commit to a review of the shutdown and its effect.

- Order all State institutions and officials to proactively provide information to the public.

- Order implementation of the UN Rabat Plan of Action, prioritising training of officials.

[1] 2015 UPR recommendations: 143.4 (Viet Nam); 143.5 (Philippines); 143.6 (Namibia); 143.7 (United States of America); 144.1 (Paraguay); 144.2 (Latvia); 144.3 (Germany); 144.4 (Hungary); 144.5 (Sierra Leone); 144.6 (Slovenia); 144.7 (Montenegro) (Poland); 144.8 (Lithuania); 144.9 (Spain); 144.10 (Estonia) (Ghana); 144.11 (Greece); 144.12 (Bahrain); 144.13 (Switzerland); 144.15 (Algeria) (Libya); 144.17 (Turkey); 144.18 (Sudan); 144.19 (Brazil); 144.20 (Italy); 144.21 (Luxembourg); 144.22 (Georgia).

[2] The Union Minister for International Cooperation informed the UN HRC 40th Session on 26 February 2019 that the government intended to sign the ICCPR in 2019. The Myanmar representative also informed exactly the same to the Special Rapporteurs for Myanmar and for freedom of opinion and expression on 8 May 2019. The Union Minister informed parliament of the government’s intention on 10 September 2019.

[3] Myanmar Times (12 September 2019) “Parliament rejects motion to join international civil rights treaty” https://www.mmtimes.com/news/parliament-rejects-motion-join-international-civil-rights-treaty.html

[4] UPR 2015: 143.51 (Republic of Korea); 143.52 (Chile); 143.50 (Turkey); 144.333 (Guatemala); 144.34 (Montenegro); 144.35 (Senegal); 144.36 (Uruguay); 144.37 (Cyprus); 144.38 (Latvia); 145.9 (Ireland).

[5] UPR 2015: 145.7 (Bahrain).

[6] FEM (11 April 2019) “20 expert organisations urge Myanmar to fully guarantee the internationally protected right to freedom of expression in the Constitution” https://freeexpressionmyanmar.org/20-expert-organisations-urge-myanmar-to-fully-guarantee-the-internationally-protected-right-to-freedom-of-expression-in-the-constitution/

[7] Translation of the Committee’s final recommendations: http://constitutionnet.org/sites/default/files/2019-07/Amendment%20Annex%20English%20Translation.pdf

[8] UPR 2015: 143.20 (Portugal); 143.33 (Nicaragua)

[9] FEM (6 March 2019) “NGOs call on parliament to consult on draft privacy law amendment” https://freeexpressionmyanmar.org/ngos-call-on-parliament-to-consult-on-draft-privacy-law-amendment/

[10] FEM (6 March 2019) “NGOs call on parliament to consult on draft privacy law amendment” https://freeexpressionmyanmar.org/ngos-call-on-parliament-to-consult-on-draft-privacy-law-amendment/

[11] UPR 2015: 143.86 (Singapore); 144.74 (Hungary); 143.48 (Republic of Korea).

[12] FEM (3 May 2020) “Myanmar’s media not free or fair” https://freeexpressionmyanmar.org/myanmars-media-not-free-or-fair/

[13] UPR 2015: 143.42 (Nepal), 143.43 (Egypt), 143.44 (Chile), 143,45 (Senegal), 143.46 (Portugal), 143.47 (Sierra Leone), 144.31 (Thailand), 143.48 (Republic of Korea).

[14] FEM (19 August 2019) “5 gaps in MNHRC’s draft Strategic Plan” https://freeexpressionmyanmar.org/5-gaps-in-mnhrcs-draft-strategic-plan/

[15] UPR 2015: 145.23 (Uruguay); 143.99 (Italy); 143.82 (Argentina); 145.28 (Saudi Arabia); 143.78 (Iceland); 143.81 (Lithuania); 143.77 (Finland); 144.82 (Chile); 144.83 (Norway).

[16] FEM (2 May 2018) “Myanmar’s media freedom at risk” https://freeexpressionmyanmar.org/myanmars-media-freedom-at-risk/

[17] These include: Soe Moe Tun, killed 13/12/2016; Aung Kyaw Naing “Par Gyi”, killed 4/10/2014; Kenji Nagai, killed 27/9/2007; Tha Win, killed 2/10/1999; Hla Han, killed 27/9/1999. FEM (2 November 2019) “5 killed journalists remembered on International Impunity Day” https://freeexpressionmyanmar.org/5-killed-journalists-remembered-on-international-impunity-day/

[18] FEM (3 May 2020) “Myanmar’s media not free or fair” https://freeexpressionmyanmar.org/myanmars-media-not-free-or-fair/

[19] UPR 2015: 144.80 (Belgium); 144.81 (Ghana); 145.31 (Austria); 145.32 (Latvia); 143.98 (New Zealand); 143.99 (Italy); 144.83 (Norway); 143.88 (Botswana).

[20] FEM (3 May 2020) “Myanmar’s media not free or fair” https://freeexpressionmyanmar.org/myanmars-media-not-free-or-fair/

[21] FEM (16 January 2017) “News Media Law” https://freeexpressionmyanmar.org/news-media-law/

[22] FEM (20 February 2017) “Printing and Publishing Law” https://freeexpressionmyanmar.org/printing-and-publishing-law/

[23] FEM (13 September 2018) “Superficial amendment leaves Broadcasting Law undemocratic” https://freeexpressionmyanmar.org/superficial-amendment-leaves-broadcasting-law-undemocratic/

[24] FEM (25 September 2018) “New bylaws are opportunity to fix Broadcasting Law flaws” https://freeexpressionmyanmar.org/new-bylaws-are-opportunity-to-fix-broadcasting-law-flaws/

[25] FEM (27 February 2017) “Broadcasting Law” https://freeexpressionmyanmar.org/broadcasting-law/

[26] FEM (3 May 2020) “Myanmar’s media not free or fair” https://freeexpressionmyanmar.org/myanmars-media-not-free-or-fair/

[27] FEM (7 May 2019) “FEM welcomes release of Reuters journalists, Wa Lone and Kyaw Soe Oo” https://freeexpressionmyanmar.org/fem-welcomes-release-of-reuters-journalists-wa-lone-and-kyaw-soe-oo/

[28] FEM (3 September 2018) “Show-trial convicts Reuters journalists to 7 years imprisonment” https://freeexpressionmyanmar.org/show-trial-convicts-reuters-journalists-to-imprisonment/

[29] FEM (9 July 2018) “Reuters case encourages mass self-censorship about Rakhine conflict” https://freeexpressionmyanmar.org/reuters-case-encourages-mass-self-censorship-about-rakhine-conflict-reuters/

[30] FEM (3 May 2020) “Myanmar’s media not free or fair” https://freeexpressionmyanmar.org/myanmars-media-not-free-or-fair/

[31] FEM (3 May 2019) “Defamation? International standards and Myanmar’s legal framework” https://freeexpressionmyanmar.org/defamation-international-standards-and-myanmars-legal-framework/

[32] FEM (3 May 2020) “Myanmar’s media not free or fair” https://freeexpressionmyanmar.org/myanmars-media-not-free-or-fair/

[33] FEM (3 May 2019) “Defamation? International standards and Myanmar’s legal framework” https://freeexpressionmyanmar.org/defamation-international-standards-and-myanmars-legal-framework/

[34] FEM (11 December 2017) “66(d) no real change” https://freeexpressionmyanmar.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/66d-no-real-change.pdf

[35] FEM (3 May 2019) “Defamation? International standards and Myanmar’s legal framework” https://freeexpressionmyanmar.org/defamation-international-standards-and-myanmars-legal-framework/

[36] FEM (24 June 2017) “Coalition statement calling for repeal of 66(d)” https://freeexpressionmyanmar.org/coalition-statement-calling-for-repeal-of-66d/; FEM (29 June 2017) “Joint statement with Amnesty to repeal 66(d)” https://freeexpressionmyanmar.org/joint-statement-with-amnesty-to-repeal-66d/; FEM (13 July 2017) “Repeal 66(d) to protect legal constitutionality, non-duplication and clarity” https://freeexpressionmyanmar.org/repeal-66d-to-protect-legal-constitutionality-non-duplication-and-clarity/

[37] Telecommunications Law and the Anti-Corruption Law: FEM (3 May 2019) “Defamation? International standards and Myanmar’s legal framework” https://freeexpressionmyanmar.org/defamation-international-standards-and-myanmars-legal-framework/

[38] FEM (2020) “Law Protecting the Privacy and Security of Citizens” https://freeexpressionmyanmar.org/laws/law-protecting-the-privacy-and-security-of-citizens/

[39] FEM (6 March 2019) “NGOs call on parliament to consult on draft privacy law amendment” https://freeexpressionmyanmar.org/ngos-call-on-parliament-to-consult-on-draft-privacy-law-amendment/

[40] FEM – published in Frontier Myanmar journal (15 September 2017) “The 66(d) amendment: tinkering at the edges” https://www.frontiermyanmar.net/en/the-66d-amendment-tinkering-at-the-edges/

[41] UPR 2015: 144.31 (Thailand).

[42] FEM (3 May 2020) “Myanmar’s media not free or fair” https://freeexpressionmyanmar.org/myanmars-media-not-free-or-fair/

[43] UPR 2015: 145.32 (Latvia).

[44] FEM (22 January 2018) “3rd Digital Rights Forum calls for better regulated, freer, safer online space” https://freeexpressionmyanmar.org/3rd-digital-rights-forum-calls-for-better-regulated-freer-safer-online-space/

[45] FEM (1 January 2017) “Telecommunications Law” https://freeexpressionmyanmar.org/telecommunications-law/

[46] FEM (2020) “Law Protecting the Privacy and Security of Citizens” https://freeexpressionmyanmar.org/laws/law-protecting-the-privacy-and-security-of-citizens/

[47] FEM (27 February 2017) “Electronic Transactions Law” https://freeexpressionmyanmar.org/electronic-transactions-law/

[48] FEM (6 March 2019) “NGOs call on parliament to consult on draft privacy law amendment” https://freeexpressionmyanmar.org/ngos-call-on-parliament-to-consult-on-draft-privacy-law-amendment/

[49] FEM (5 November 2019) “Freedom of the Net: Myanmar in 2019” https://freeexpressionmyanmar.org/freedom-of-the-net-myanmar-in-2019/

[50] FEM (5 November 2019) “Freedom of the Net: Myanmar in 2019” https://freeexpressionmyanmar.org/freedom-of-the-net-myanmar-in-2019/

[51] FEM (29 April 2020) “Deactivating SIM cards during Covid-19 violates rights — Covid 19” https://freeexpressionmyanmar.org/deactivating-sim-cards-during-covid-19-violates-rights-covid-19/

[52] FEM (5 November 2019) “Freedom of the Net: Myanmar in 2019” https://freeexpressionmyanmar.org/freedom-of-the-net-myanmar-in-2019/

[53] FEM (24 June 2019) “Internet Shutdown in Rakhine and Chin States” https://freeexpressionmyanmar.org/internet-shutdown-in-rakhine-and-chin-states/

[54] FEM (24 June 2019) “Internet Shutdown in Rakhine and Chin States” https://freeexpressionmyanmar.org/internet-shutdown-in-rakhine-and-chin-states/

[55] FEM (21 December 2019) “Joint statement condemning one of the world’s longest internet shutdowns in Rakhine State” https://freeexpressionmyanmar.org/joint-statement-condemning-one-of-the-worlds-longest-internet-shutdowns-in-rakhine-state/ and FEM (22 May 2020) “Multi-stakeholder webinar on Myanmar’s website blocking and shutdown” https://freeexpressionmyanmar.org/multi-stakeholder-webinar-on-myanmars-website-blocking-and-shutdown/

[56] FEM (21 June 2020) “Civil society marks 1-year of world’s longest internet shutdown” https://freeexpressionmyanmar.org/civil-society-marks-1-year-of-worlds-longest-internet-shutdown/

[57] FEM (2 April 2020) “250 organisations condemn Myanmar government order to block websites” https://freeexpressionmyanmar.org/250-organisations-condemn-myanmar-government-order-to-block-websites/

[58] FEM (2 April 2020) “250 organisations condemn Myanmar government order to block websites” https://freeexpressionmyanmar.org/250-organisations-condemn-myanmar-government-order-to-block-websites/

[59] UPR 2015: 144.84 (Brazil); 145.33 (France); 145.34 (Sweden); 145.35 (Luxembourg); 145.36 (Estonia).

[60] FEM (26 March 2020) “No permission to protest” https://freeexpressionmyanmar.org/no-permission-to-protest/

[61] FEM (26 February 2018) “5 violations that need addressing in protest law amendment” https://freeexpressionmyanmar.org/5-violations-that-need-addressing-in-protest-law-amendment/

[62] FEM (15 May 2018) “Crackdown on anti-war activists shows protests still need permission” https://freeexpressionmyanmar.org/crackdown-on-anti-war-activists-shows-protests-still-need-permission/

[63] FEM (26 March 2020) “No permission to protest” https://freeexpressionmyanmar.org/no-permission-to-protest/

[64] FEM (26 March 2020) “No permission to protest” https://freeexpressionmyanmar.org/no-permission-to-protest/

[65] FEM (26 February 2018) “5 violations that need addressing in protest law amendment” https://freeexpressionmyanmar.org/5-violations-that-need-addressing-in-protest-law-amendment/

[66] FEM (26 March 2020) “No permission to protest” https://freeexpressionmyanmar.org/no-permission-to-protest/

[67] FEM (26 February 2018) “5 violations that need addressing in protest law amendment” https://freeexpressionmyanmar.org/5-violations-that-need-addressing-in-protest-law-amendment/

[68] UPR 2015: 145.23 (Uruguay); 143.99 (Italy); 144.82 (Chile); 144.83 (Norway); 145.22 (Italy).

[69] FEM (26 March 2020) “No permission to protest” https://freeexpressionmyanmar.org/no-permission-to-protest/

[70] FEM (26 March 2020) “No permission to protest” https://freeexpressionmyanmar.org/no-permission-to-protest/

[71] FEM (26 March 2020) “No permission to protest” https://freeexpressionmyanmar.org/no-permission-to-protest/

[72] FEM (26 March 2020) “No permission to protest” https://freeexpressionmyanmar.org/no-permission-to-protest/

[73] UPR 2015: 145.32 (Latvia); 143.84 (Cuba); 143.85 (Georgia).

[74] FEM (27 February 2017) “Broadcasting Law” https://freeexpressionmyanmar.org/broadcasting-law/

[75] FEM (3 May 2020) “Myanmar’s media not free or fair” https://freeexpressionmyanmar.org/myanmars-media-not-free-or-fair/

[76] FEM (24 June 2019) “Internet Shutdown in Rakhine and Chin States” https://freeexpressionmyanmar.org/internet-shutdown-in-rakhine-and-chin-states/

[77] FEM (2 April 2020) “250 organisations condemn Myanmar government order to block websites” https://freeexpressionmyanmar.org/250-organisations-condemn-myanmar-government-order-to-block-websites/

[78] FEM (3 September 2018) “Show-trial convicts Reuters journalists to 7 years imprisonment” https://freeexpressionmyanmar.org/show-trial-convicts-reuters-journalists-to-imprisonment/

[79] FEM (12 March 2020) “New National Records and Archives Law preserves government secrecy” https://freeexpressionmyanmar.org/new-national-records-and-archives-law-preserves-government-secrecy/

[80] FEM (12 March 2020) “New National Records and Archives Law preserves government secrecy” https://freeexpressionmyanmar.org/new-national-records-and-archives-law-preserves-government-secrecy/

[81] FEM (18 July 2019) “New Bill a big step backwards for RTI” https://freeexpressionmyanmar.org/new-bill-a-big-step-backwards-for-rti/

[82] FEM (18 July 2019) “New Bill a big step backwards for RTI” https://freeexpressionmyanmar.org/new-bill-a-big-step-backwards-for-rti/

[83] FEM (4 April 2018) “Right to truth” https://freeexpressionmyanmar.org/right-to-truth/

[84] FEM (3 September 2018) “Show-trial convicts Reuters journalists to 7 years imprisonment” https://freeexpressionmyanmar.org/show-trial-convicts-reuters-journalists-to-imprisonment/

[85] FEM (3 May 2019) “Defamation? International standards and Myanmar’s legal framework” https://freeexpressionmyanmar.org/defamation-international-standards-and-myanmars-legal-framework/

[86] FEM (6 March 2019) “NGOs call on parliament to consult on draft privacy law amendment” https://freeexpressionmyanmar.org/ngos-call-on-parliament-to-consult-on-draft-privacy-law-amendment/

[87] FEM (25 February 2020) “Proposed bill will punish government staff who release information about Corona” https://www.facebook.com/FreeExpressionMyanmar/posts/2723452031101702

[88] FEM (5 November 2019) “Freedom of the Net: Myanmar in 2019” https://freeexpressionmyanmar.org/freedom-of-the-net-myanmar-in-2019/

[89] FEM (4 April 2018) “Right to truth” https://freeexpressionmyanmar.org/right-to-truth/

[90] FEM (4 April 2018) “Right to truth” https://freeexpressionmyanmar.org/right-to-truth/

[91] These included:

- 9 recommendations to ratify ICERD: UPR 2015: 144.16 (Ghana); 144.4 (Hungary); 144.15 (Algeria) (Libya); 144.17 (Turkey); 144.18 (Sudan); 144.19 (Brazil); 145.1 (Austria); 143.9 (Egypt).

- 11 recommendations to protect women: UPR 2015: 145.14 (Lithuania); 143.63 (Japan); 143.103 (Italy); 143.56 (France); 143.53 (Pakistan); 143.57 (Austria); 143.69 (Spain); 143.68 (Serbia); 143.66 (Sweden); 143.67 (Namibia); 143.71 (Paraguay).

- 13 recommendations to protect religious minorities: UPR 2015: 143.89 (Sudan); 143.93 (Republic of Korea); 143.96 (Holy See); 143.94 (Indonesia); 143.90 (Malaysia); 143.91 (Turkey); 143.92 (China); 143.88 (Botswana); 143.97 (Poland); 145.65 (Sweden); 145.49 (Malaysia); 145.10. (Austria); 144.47 (Mexico).

- 6 recommendations to protect ethnic minorities: UPR 2015: 143.24 (Slovenia); 143.90 (Malaysia); 143.92 (China); 145.10. (Austria); 143.60 (Nepal); 143.61 (Ecuador).

- 7 recommendations to address incitement and “hate speech”: 145.12 (Norway); 143.62 (New Zealand); 145.48 (Belgium); 145.50 (Djibouti); 145.51 (Egypt); 144.51 (Algeria); 145.10 (Austria).

[92] FEM (27 March 2017) “Protection Against Hate Speech Bill” https://freeexpressionmyanmar.org/protection-against-hate-speech-bill/

[93] FEM (25 August 2017) “FEM welcomes Kofi Annan commission recommendations on media, access to information, and hate speech” https://freeexpressionmyanmar.org/fem-welcomes-kofi-annan-commission-recommendations-on-media-access-to-information-and-hate-speech/

[94] FEM (22 April 2020) “Hate speech Directive threatens free expression in election countdown” https://freeexpressionmyanmar.org/hate-speech-directive-threatens-free-expression-in-election-countdown/

[95] FEM (22 April 2020) “Hate speech Directive threatens free expression in election countdown” https://freeexpressionmyanmar.org/hate-speech-directive-threatens-free-expression-in-election-countdown/

[96] FEM – published in Irrawaddy media (28 August 2018) “Let’s talk about “hate speech”” https://burma.irrawaddy.com/news/human-rights/2018/08/28/168009.html

[97] FEM – published in Irrawaddy media (28 August 2018) “Let’s talk about “hate speech”” https://burma.irrawaddy.com/news/human-rights/2018/08/28/168009.html

[98] FEM – published in Irrawaddy media (28 August 2018) “Let’s talk about “hate speech”” https://burma.irrawaddy.com/news/human-rights/2018/08/28/168009.html

[99] FEM – published in Irrawaddy media (28 August 2018) “Let’s talk about “hate speech”” https://burma.irrawaddy.com/news/human-rights/2018/08/28/168009.html

[100] UPR 2015: 145.14 (Lithuania); 143.63 (Japan); 143.103 (Italy); 143.56 (France); 143.53 (Pakistan); 143.57 (Austria); 143.69 (Spain); 143.68 (Serbia); 143.66 (Sweden); 143.67 (Namibia); 143.71 (Paraguay).

[101] FEM (29 December 2018) ““Shut up girl, it’s too sensitive!” https://freeexpressionmyanmar.org/mdrf-invitation-shut-up-girl-its-too-sensitive/

[102] FEM (29 December 2018) ““Shut up girl, it’s too sensitive!” https://freeexpressionmyanmar.org/mdrf-invitation-shut-up-girl-its-too-sensitive/

[103] FEM (29 January 2019) “Daring to defy Myanmar’s patriarchy” https://freeexpressionmyanmar.org/daring-to-defy-myanmars-patriarchy/

[104] FEM (29 January 2019) “Daring to defy Myanmar’s patriarchy” https://freeexpressionmyanmar.org/daring-to-defy-myanmars-patriarchy/